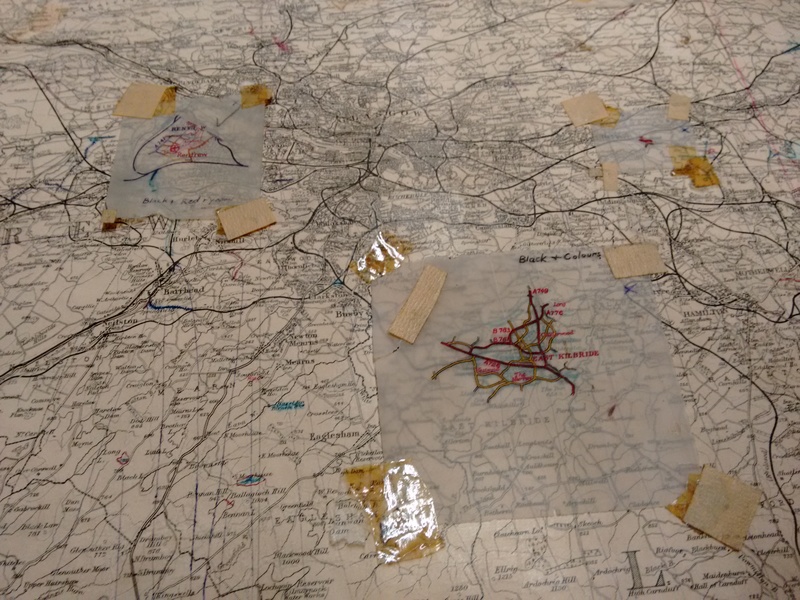

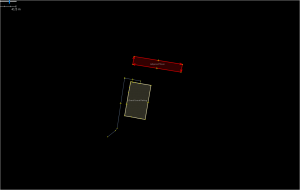

In the West Midlands our fire hydrant signs are generally placed on lamp posts:

The black H on a yellow background I believe to be a UK standard. The upper number is the diameter of the underlying water main in mm. The lower number is the distance in feet to the fire hydrant from the sign with the arrow showing the direction to the actual hydrant. There is also a reference number at the foot of the sign. So, having spotted the sign, the actual fire hydrant has to be found. The signs can get swivelled on the lamposts through maintenance interventions or general neglect and the arrows point in the wrong direction!

To complicate matters further, there are some fire hydrants that do not have a sign, and some older variants of the signs. These older signs tend to be attached to buildings or walls and I have no idea what the numbers refer to.

So you have to on the lookout on the ground as well as spotting yellow H signs.Fire hydrant covers generally have FH on them to identify them, although some older ones can have just H only. Whether the older style ones are still operational I don’t know, but they get mapped anyway.

And of course it’s always good to see public organisations collaborating successfully with each other!

The basic tag is emergency=fire_hydrant with more details on the OSM wiki

Why the sudden interest in fire hydrants? In the UK, they’ve languished as an item that gets mapped.

At our last mappamercia pub meeting Andy Mabbett regaled us with his saga of trying to get West Midlands Fire Service to release the locations of fire hydrants under Freedom of Information legislation.

The full saga can be found here

WMFS refused to release the information on the grounds of national security viz: “publishing information about water networks and other parts of the critical national infrastructure could expose vulnerabilities in the network and pose a serious risk to public health either through non availability of water resource or

contamination of supplies. There does not have to be any evidence that this is being planned but it is a possibility given the current threat level in the United Kingdom.”

An appeal by Andy against WMFS to the first-tier information rights tribunal mainly on the grounds that other Fire Services in the UK had already released their information on fire hydrants was rejected. The judges agreed with the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) assessment:

“The ICO concluded that the withholding of the information was reasonably necessary for national security and a listing of hydrants and their locations would assist in the planning of an attack by poisoning on water supply infrastructure by identifying access points. Such an attack on the infrastructure would be in the domain of national security. While hydrants are visible a comprehensive list of the precise location of every hydrant would place in the public domain more information than is available through hydrants being visible. WMFS supplied a list of attacks and attempted attacks on water supplies.The ICO considered that such an attack was plausible.”

There is a method for contaminating the water supply known as backflow contamination, which is considered to be reasonably easy according to an excellent paper here which quotes extensively from US military and homeland security sources. Fire hydrants are one possible source to generate backflow.

My limited understanding of water networks is that backflow is a general problem for the water supply industry, which can mitigate the effects with backflow prevention devices. Just how extensive and successful this mitigation is in the UK (and thus how safe we are from backflow attacks) will remain a commercial mystery, as our water supply is in the hands of private companies who are under no obligation to reveal such information. ( I have another story about water networks and open information which will be the subject of a later blog)

Given the cult of secrecy that exists at all levels of official Britain, it also seems unlikely there will be any disclosure of the risk levels of such an attack vector so that we might make up our own minds based on the data. We will have to make do with the assurances of “those that know best”. The public’s role seems to be limited primarily to that of potential or actual victims.

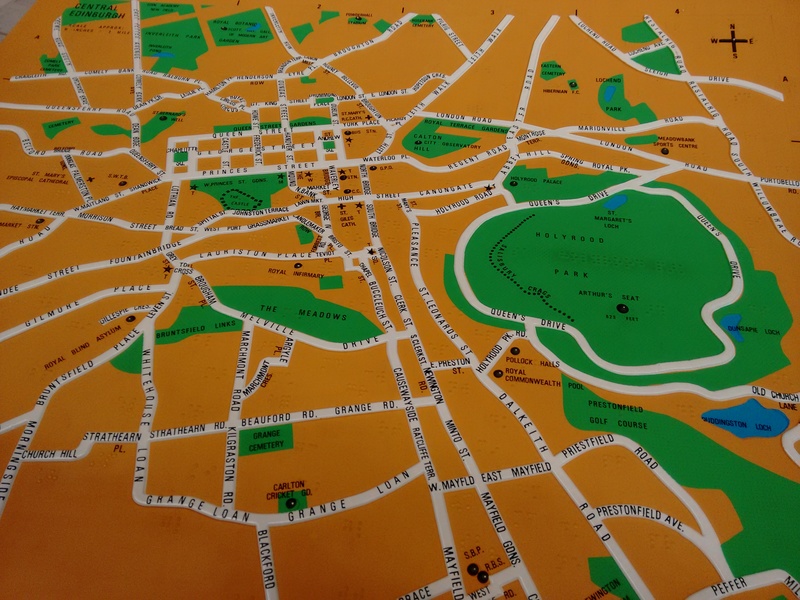

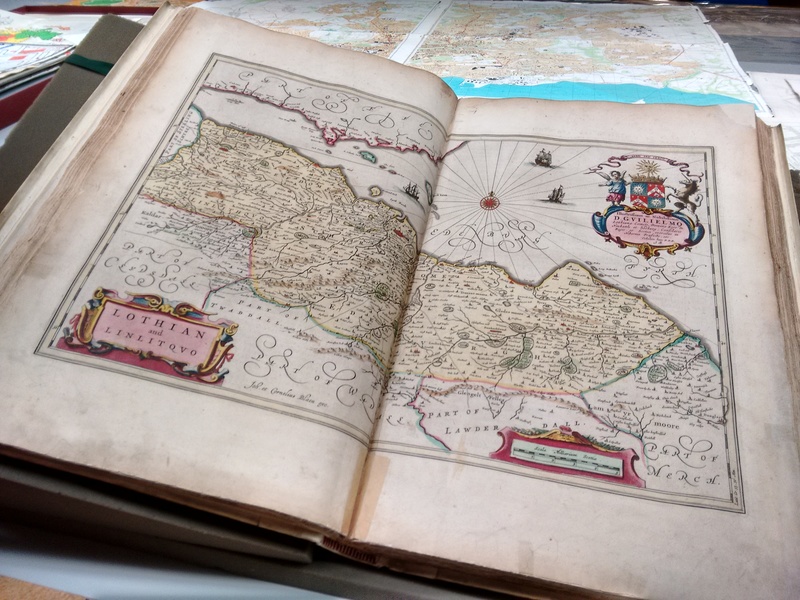

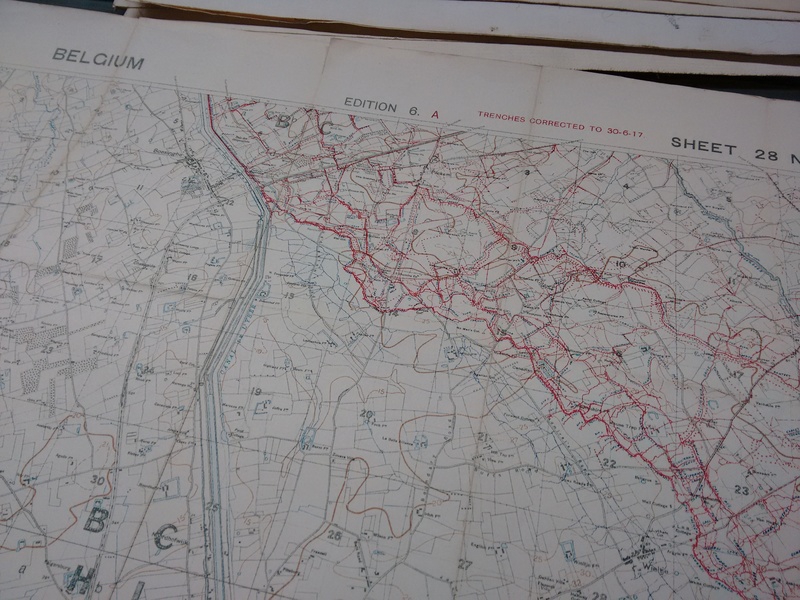

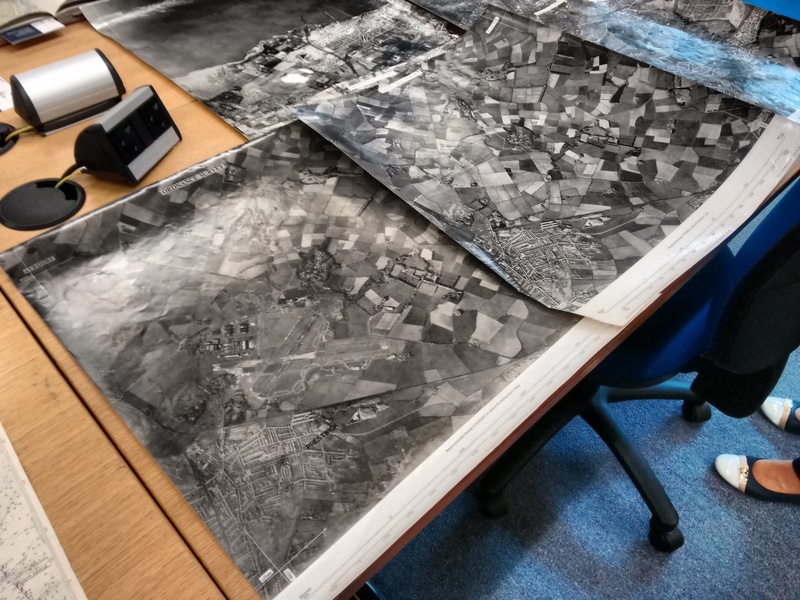

This issue does raise some interesting ethical challenges for OpenStreetMap as it seems to be sending us back several centuries when accurate maps were regarded as military secrets. Or to the days of the Cold War when our national mapping agency the Ordnance Survey would obligingly leave blank spaces on their maps at the sites of military installations. Would a map of fire hydrants in the West Midlands be construed as offence under ss57&58 of the Terrorism Act 2000: collecting, possessing or making a record of information of a kind likely to be useful to a person committing or preparing an act of terrorism? Should we be standing up for opendata, one of the founding principles of OpenStreetMap, or protecting (supposedly) national security? What is the position in other jurisdictions where there are more draconian restrictions about identifying and mapping military installations and “national critical infrastructure”? Are mappers more circumspect there? What’s the legal postion- is the OSMF liable for prosecution or just the contributing mapper or both? Should OSMF comply with a demand to remove information on the grounds of national security? Or to refrain from collecting it in the first instance?

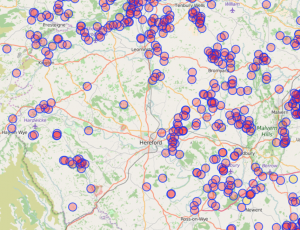

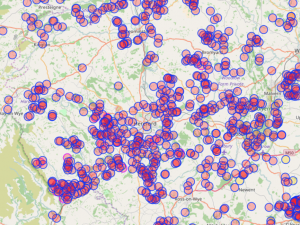

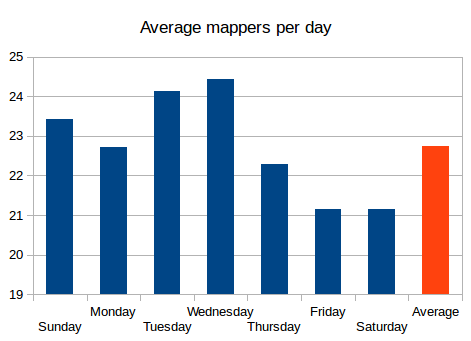

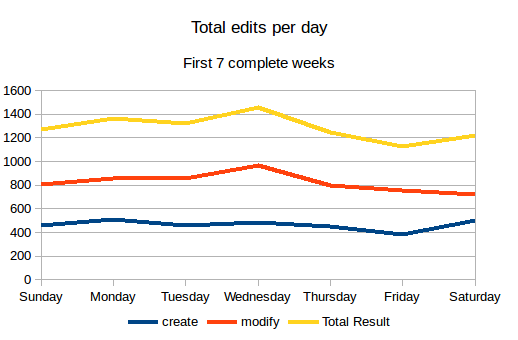

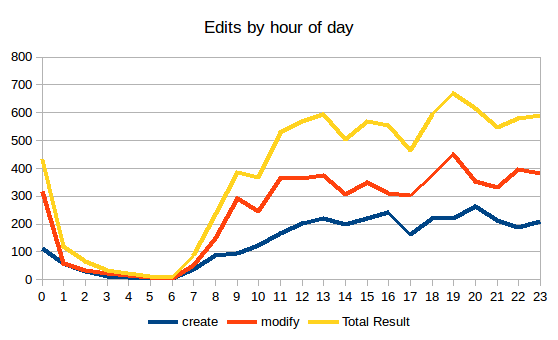

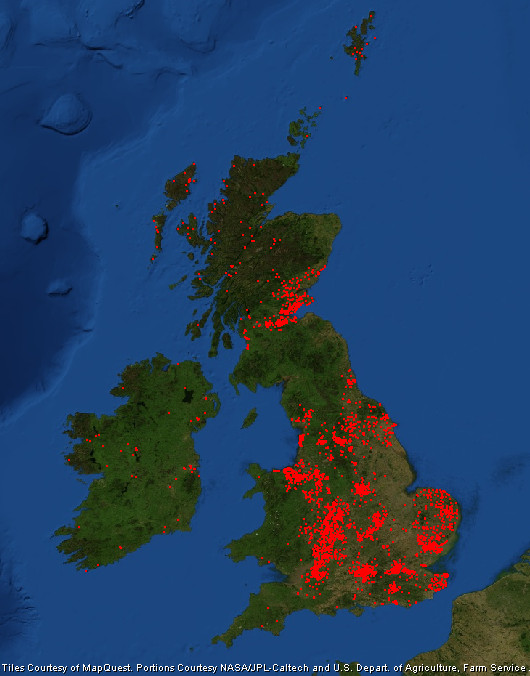

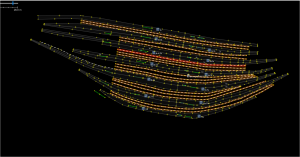

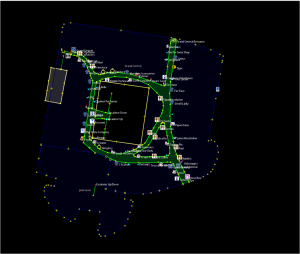

According to taginfo there are only 1786 fire hydrants mapped in the UK, of which there are now about 300 in the West Midlands. Prior to my interest being piqued by this sorry tale there were only about 5 fire hydrants mapped in the West Midlands. Judging by the density of fire hydrants I’ve discovered so far, there are probably thousands in the West Midlands so I seriously doubt whether we’ll ever crowdsource the location of all of them,(or even many more than we have already).

Nonetheless, it’s been an education in another aspect of urban infrastructure I wasn’t really aware of, and a confirmation of the patrician “you don’t need to know about that” attitude of much of British officialdom.

(all of the images are my own and are published here as public domain)